What We Learned From 5 Million GLP-1 Scripts

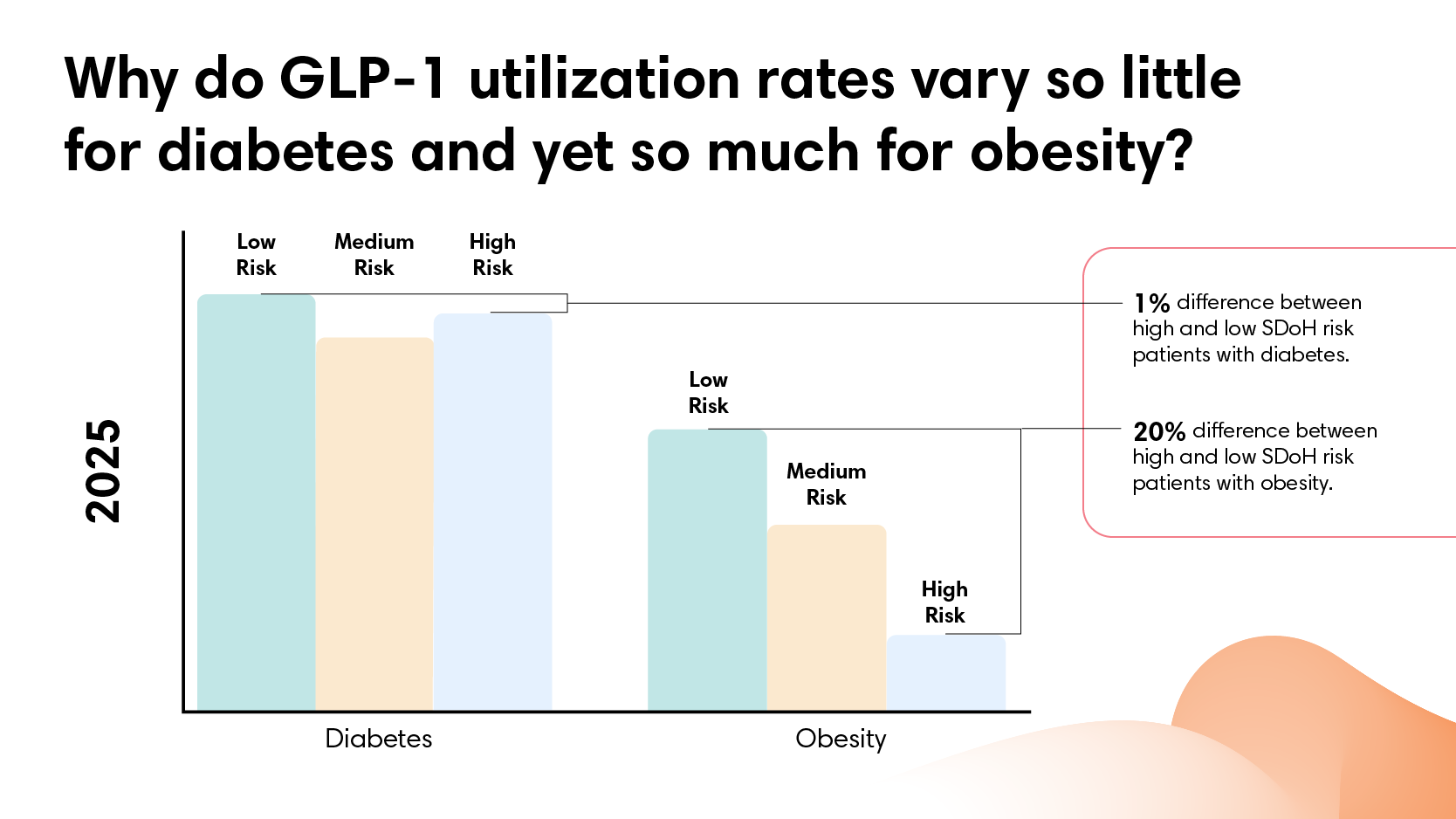

We looked at 5M GLP-1 prescriptions over two years and thousands of patients by SDOH risk. It raised an open question: why does GLP-1 utilization vary so much more for obesity than diabetes? HINT: finances may not tell the whole story.

GLP-1 coverage works for diabetes. For obesity, it doesn't.

GLP-1 use has surged over the past two years. The medications demonstrate real clinical effectiveness for both diabetes and obesity.

As utilization grows, so do questions about who gets treated. The assumption often runs that access follows affluence: people with more resources have an easier time getting these medications. Does that pattern hold? And does it hold equally across different diagnoses?

Our analysis covers nearly 5 million GLP-1 prescriptions across two years of employer-sponsored health coverage. Everyone in this dataset has insurance. What varies is neighborhood context.

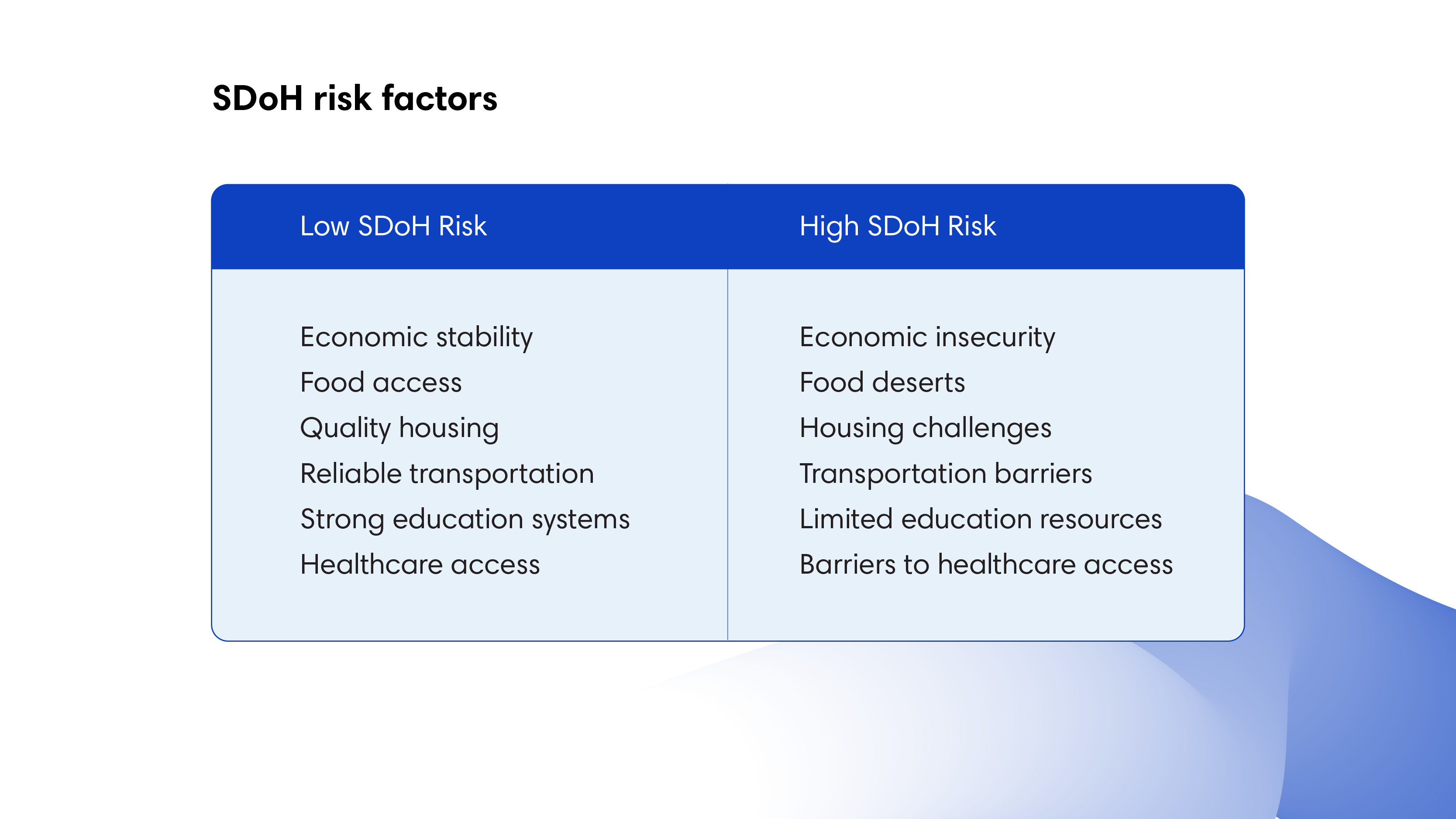

Social determinants of health (SDoH) provide our measurement framework: a score capturing economic stability, food access, housing quality, transportation access, education levels, and healthcare resources at the neighborhood level. SDoH impact doesn’t depend on income alone. Two people might earn similar salaries but live in very different environments in terms of easy access to grocery stores, transit options, or proximity to healthcare. SDoH risk scores capture that broader picture.

What We Found

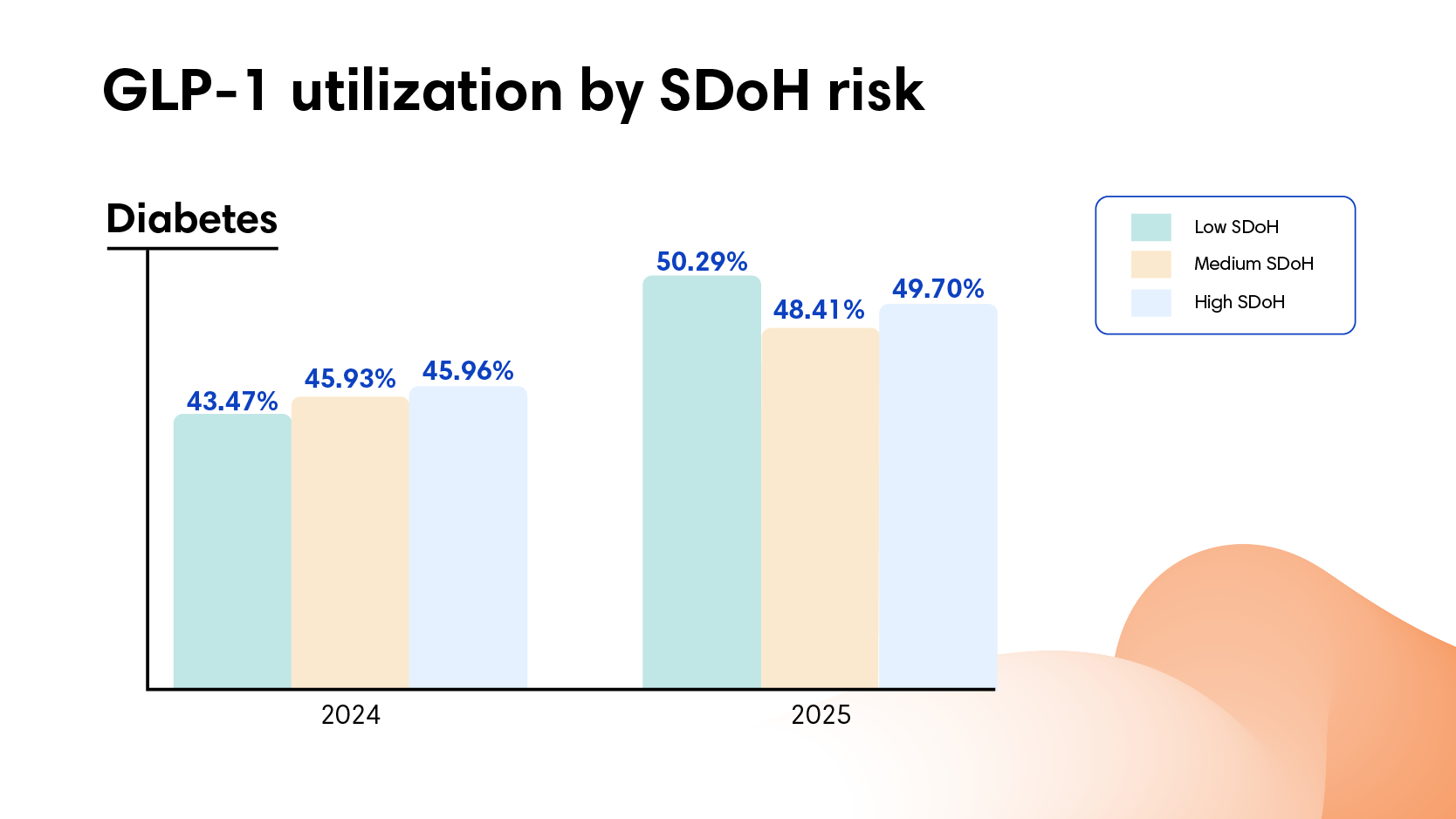

For diabetes, GLP-1 utilization was consistent across all neighborhoods. In 2024, 43% of people with diabetes in neighborhoods with lower SDoH risk filled GLP-1 prescriptions, compared to 46% in neighborhoods with higher SDoH risk. In 2025, GLP-1 utilization rates rose to 48% and 50%, respectively. No meaningful disparity. If anything, people in neighborhoods with higher SDoH risk filled prescriptions at slightly higher rates.

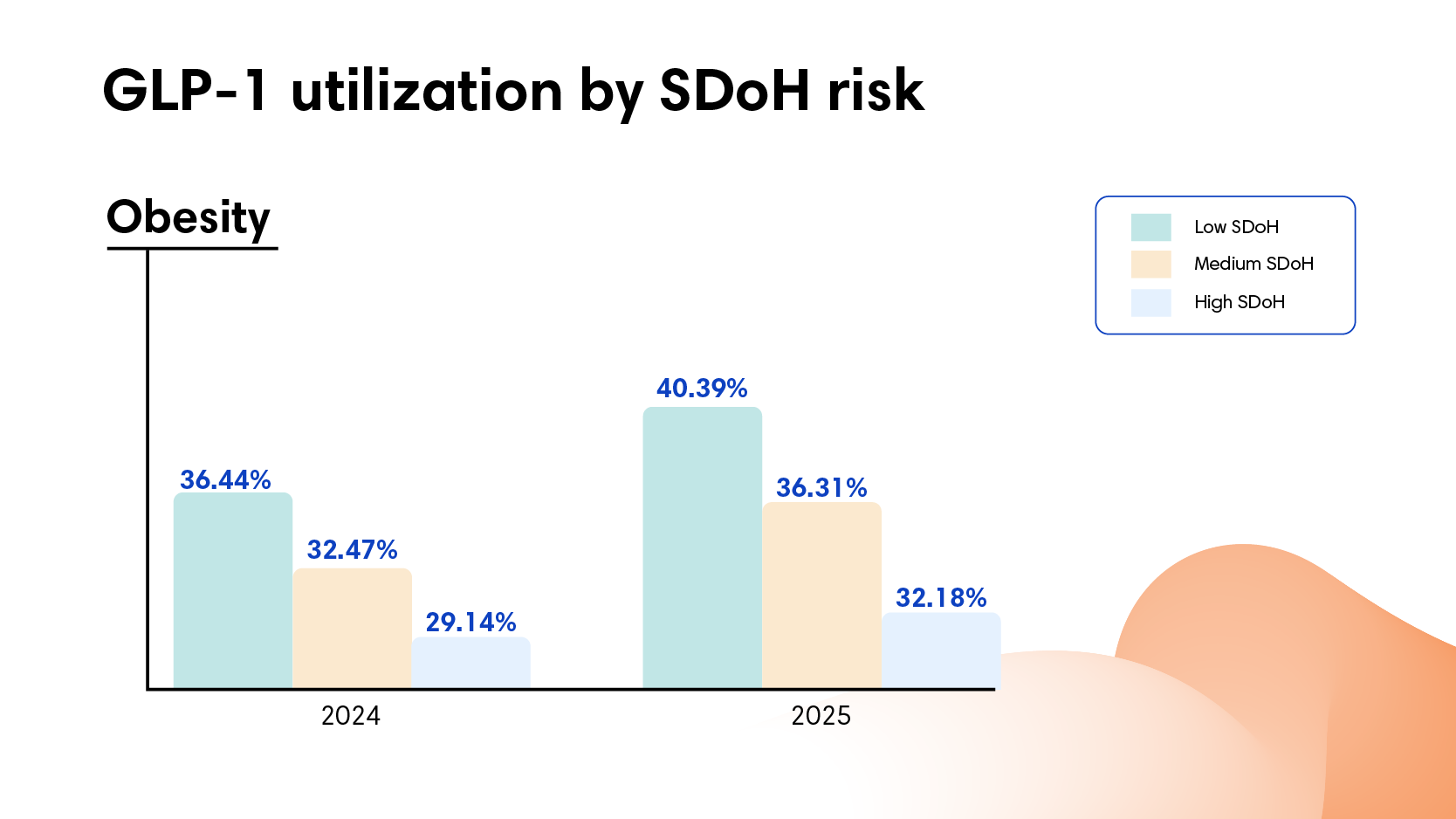

For obesity, the pattern reversed. Utilization dropped as SDoH risk increased. In 2024, 36% of people with obesity in low-risk neighborhoods filled GLP-1 prescriptions compared to 29% in high-risk neighborhoods. In 2025, utilization increased across all neighborhoods, and yet the gap persisted: 40% versus 32%. People with obesity in neighborhoods with higher SDoH risk consistently filled prescriptions at rates roughly 20% lower than those in neighborhoods with lower SDoH risk.

That divide holds steady at roughly 8 percentage points across both years. In low-risk neighborhoods, 4 out of 10 people with obesity filled prescriptions. In high-risk neighborhoods, only 3 out of 10.

Disease prevalence makes this pattern more striking. Diabetes rates run twice as high in high-risk neighborhoods (26 per 1,000 people compared to 12 per 1,000). And obesity rates run 40% higher (14 per 1,000 compared to 10 per 1,000). The populations carrying the highest disease burden show equal utilization for diabetes and lower utilization for obesity.

Why the Split Exists

Everyone in this dataset has employer-sponsored insurance. The diabetes pattern rules out a straightforward access problem. If high neighborhood SDoH risk generally prevented people from filling prescriptions or accessing GLP-1 medications, we'd see that pattern for both conditions. We don't.

Out-of-pocket costs are higher for obesity treatment, roughly $10-15 more per script than diabetes treatment.

However, that difference alone isn’t large enough to explain the utilization gap. Across all neighborhoods, people in high-risk areas actually pay less out of pocket for both diabetes and obesity GLP-1s than those in low-risk areas. Yet diabetes utilization stays flat while obesity utilization drops. The modest cost premium for obesity treatment likely plays a role, but other barriers must be creating the divide.

Something specific to obesity treatment drives the disparity. What that is could vary: how providers frame the treatment, prior authorization requirements, documentation needed to maintain coverage, or how patients advocate for themselves. We can't pinpoint which factors drive the gap from this data alone.

What the data does show: the pattern repeats across two years and holds steady. Diabetes treatment translates consistently from coverage to filled prescriptions. Obesity treatment doesn't.

What It Means

The cost implications run in two directions.

First, employers with populations in high SDoH risk areas face significantly higher GLP-1 costs overall—not because of unequal prescribing, but because of higher disease burden. They pay for 70% more GLP-1 prescriptions per capita (109 scripts per 1,000 members compared to 65 per 1,000) because twice as many people have diabetes to begin with.

Second, the obesity utilization gap may signal missed prevention opportunities. Individuals who don't receive obesity treatment today are more likely to progress to diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or orthopedic conditions that require more intensive and expensive care later. The spend isn't avoided. It's deferred and amplified.

The Bottom Line

Across two years and 5 million prescriptions, the same insurance coverage produces equal diabetes utilization regardless of SDoH risk, but unequal obesity utilization. The split reveals something specific: this isn't a general access problem. Where diabetes treatment translates consistently from coverage to filled prescriptions, obesity treatment creates gaps that follow neighborhood disadvantage.

Learn more about how we measure social determinants of health and why our methodology captures neighborhood context more completely.

Want to understand how neighborhood factors affect healthcare utilization in your population? Contact us.